Can green finance and pressure from green investors help make Indian agriculture more sustainable?

Let’s look at two major Indian agricultural investment needs: adequate water supply for agriculture and maintaining soil conditions.

Water, water everywhere and not a drop to eat

Water availability can be a major constraint on Indian agriculture. Over the period 2010-2019, 85 of India’s 718 districts (zila) suffered droughts. Investment is needed to capture and retain water in watersheds during the monsoon before releasing it in the dry season. Good water management has the added bonus of reducing soil loss ensuring its fertility.

In 2000, demand for water (three-quarters of which is used for agriculture) was 634 billion cubic metres (BCM). To meet this demand, India abstracted 253 BCM from the groundwater, much of it unsustainably. Policies like allowing farmers to sink unregulated boreholes, and providing farmers with free electricity for pumping encourages over-exploitation of groundwater. The problem is not a shortage of rain per se, India’s annual average is 4000 BCM. But lack of storage, topography and location means that only 690 BCM of surface water is available for use.

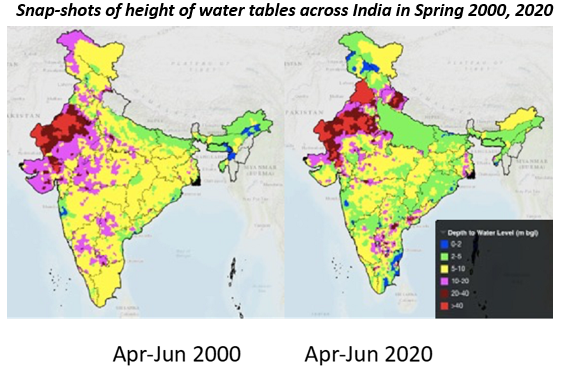

But not every state is mismanaging groundwater. In some areas investment in watershed development is producing real benefits. The figure below shows how different states’ water tables have changed over the last 20 years. However, in a fifth of India’s groundwater assessment units, especially in the states of Punjab, Rajasthan and Haryana, extraction exceeds recharge. In these states water is not being sustainably used, it is being mined. The good news is some other states are seeing rising water tables.

Water management is being quietly transformed by collective investment in small, engineered changes in watersheds and changes in agricultural practices. These reduce the cultivation of water-hungry crops, like sugar cane or paddy rice, in water-stressed areas. The engineered changes make use of relatively simple technologies and local materials to improve the retention of water in the soil and extend the span of months over which water is available for use beyond the monsoon.

Making running water, walk and sink underground

Building on the success of the Indo-German Watershed Development Program implemented by NABARD and the Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR) through NGOs and village organisations, the Indian government instituted the Watershed Development Fund (WDF) at NABARD in 1999-2000 to up-scale the approach across India. Earlier programmes had been more limited in their approach - Drought Prone Areas Programme and the Desert Development Programme. The motivation of all of these is the same: soil conservation, flood protection, drought-proofing, increasing yields by better soil moisture and restoring degraded lands. Watershed development typically uses a ridge to valley approach to catch rainfall high in the watershed thereby regenerating land, conserving soil and enhancing green cover.

These schemes apply intermediate technologies: constructing boulder dams to slow the flow of streams to increase the rate of percolation into the water-table, constructing ditches/bunds on hillsides faithfully following the hillside’s contours to stop soil erosion and planting trees on these contours to help stabilise them. Each project is small and can be delivered by local farmers working together during the quieter time of the agricultural year. These techniques can be taught to farmers and use easily accessed materials and equipment like local stones and indigenous trees.

The net effect of these interventions is to increase the amount of rainwater retained in the water table or surface ponds following the monsoon rather than losing it to the sea. Such watershed development projects emphasise the role of community and grassroots organisations in making and maintaining these water harvesting structures. One of the NGOs that has been active since 1993 is the Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR). It undertook an evaluation of the benefits from watershed development projects in terms of different ecosystem services and the benefit to cost ratios for four villages in Madhya Pradesh that had the ‘treatment’ and four control villages. The study found a significant but highly variable reduction in the amount of ‘soil carbon detachment’ from soil erosion, higher crop productivity and reduced time needed for water collection by villagers (higher water tables) than the controls.

Financing watershed development

While the Indian and state governments are the principal sources of funding for watershed development, notably, the Integrated Watershed Development Program (IWMP), NABARD through the WDF and related schemes is an important player in this field, also engaging with civil society agencies. According to its Annual Report for 2019-20, there are 231 ongoing projects that cover almost 10 lakh hectares and disbursing loans or grants to states of Rs 82 cr (USD 6.1 m). State government also contributes to watershed development costs. State spending is subsumed in the Rs 66 cr budget line for flood control & irrigation (data aggregated from state budgets).

There are challenges to drawing in private sector money. Watershed development is the quintessential public good. It benefits all the people in the watershed regardless of whether they personally contribute to the communal effort to finance, build and maintain the structures. It also benefits urban areas by increasing the availability of potable water, reducing damage from flash floods and improving the reliability of hydropower schemes. Economists worry that beneficiaries can ‘free-ride’ from their neighbours’ efforts. Such market failure means that such projects will be under-financed by private capital relative to their benefit to society. There is some private sector capital investment chiefly from India’s CSR obligations mandated under the Companies Act 2013.

As a result, investment has been through the public sector, foreign aid or impact investors not looking for a monetary income return and better able to tap into the village’s social capital. In one review of policies to promote Ecosystem-based adaptation investment, the researchers found that there was a plethora of policies and programmes that sought to implement watershed development however the objectives of different schemes rarely take a community-centric, ridge to valley strategic view of watersheds.

One intriguing possibility is some sort of hybrid model where capital is raised to finance the upstream labour and material costs and the interest repaid through charges on the downstream beneficiaries who avoid damage costs. There are examples of such payments for watershed services In New York (Catskill and Delaware Rivers).

Farming through nature, not against it

Andhra Pradesh’s Community Managed Natural Farming (CMNF) programme is based on the philosophy that soil nutrition and pest control should be supplied by ecological processes, and not through synthetic chemicals. CMNF relies on a symbiotic relationship between fungal mycorrhiza and crop plants through which crop roots supply fungi with energy and fungi liberate nutrients from soil particles. This is supplemented by nitrogen fixed by legumes like peas intercropped or grown as break crops.

The farmer’s main role is creating the appropriate environment based on traditional Indian agricultural practices. The regime includes farmers ensuring the soil has a diverse, year-round vegetative cover (achhadana) and retains a non-compacted, aerated structure (waaphasa). Farmers apply organic inputs derived from cattle (jeevamrutham) and microbial inoculants to the seed (beejamrutham).

In 2016, Andhra Pradesh established the Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (RySS) - a state-owned, non-profit organisation to develop and spread CMNF through the state. The objective is to create a transformative business model for climate-resilient and farmer-focused agriculture in India. It intends to shift all farms of Andhra Pradesh to natural farming. To date, 5 lakh farmers apply CMNF techniques in Andhra Pradesh.

The plan is to reach 60 lakh farmers in 13,000 gram panchayats (village councils) by 2024 and the state’s entire 8 million hectare area by 2026. Most farms in the state are female-owned and smaller than a hectare, many are in remote areas. Reaching the diverse communities needs substantial investment in the institutional set-up to educate, communicate and provide easily accessed farmer services (like agricultural inputs and sites to make and distribute organic farm inputs). Scaling up starts from the female self-help groups, brigaded into successively larger aggregates for a different type of support (information, loans to purchase equipment, paid external staff).

Impressive increases in net margins for farmers from reduced costs

RySS analysed farms’ costs and revenues in 2019-2020. It found:

- For paddy rice, the paid out costs fell by Rs 2318 and farmers’ income rose by 8%.

- For maize, the yield under CMNF increased by 36% and the net income increased by 111%.

- For groundnut, the yield under CMNF increased by 14% and the net returns increased by 41%.

- In the case of cotton the net income increased by 45%

- For tomato the net income increased by 41%.

An independent study by the Institute of Development Studies in Andhra Pradesh, on 2000+ sample shows that the paid-out costs in natural farming fell by Rs 26,155 per hectare and net returns increased by Rs 26,799 per hectare. This suggests that once the farm’s soil ecosystem has its natural fertility restored CMNF can generate net revenue gains.

Mainstreaming CMNF in Andhra Pradesh

The programme aims to create half a million farmer groups and 25000 village level federations, by 2026. Three factors inhibit the rate of farmer adoption. Firstly, there is a decline in yield during the initial 2-3 years while soil fertility builds up, secondly, there is a limited number of customers aware of the novel and potentially sought after production methods and, thirdly most modern farmers need to be trained to apply the CMNF regime.

RySS estimate the cost of scaling-up CMNF across Andhra Pradesh will require USD 2.3 billion. Investments through green finance or climate-resilient bonds could be used for supporting with transformation and scaling up in the following ways:

- Providing payments to help farmers cope with losses (due to lower productivity, higher risks of pest attack, and also higher labour requirements) incurred in the initial conversion period and also to support farmers who are dependent only on agriculture for their livelihood, during the transition period.

- Investing in the creation of market linkages to support farmers to connect with markets in cities, and help them in realising the best price for their produce.

- Investing into capacity building, to train the farmers and make them aware of the processes under CMNF

- Investing into certain on-farm and off-farm processes related to storage, aggregation, livestock support etc. for converted farmers whose incomes and yields have been stabilised or improved.

The Last Word

Making India’s agricultural system more resilient to climate change requires making changes that are at the same time novel and extremely traditional. But it also means applying finance in a different way. Like the mutualistic relationship between fungi and root, the public and private sector need to work to ensure finances flows from the capital markets, through public spending to the small-scale projects that can transform rural livelihoods.

Read our previous blogs on making Indian agriculture resilient from February and April to find out more.

'Til next time!

Climate Bonds