Opportunity for public & private investment to deliver agri-resilience in India

The world has watched farmers protest on the outskirts of New Delhi, since November, standing against India’s new farm legislation rushed through Parliament months earlier.

Protesting farmers are concerned these reforms represent an effort by government to scale back its role in food markets and throw them into the jaws of corporations. At the heart of these protests is the issue of high level of risks associated with farming in India as farmers are subject to low and volatile incomes.

These laws liberalised inter-state trade, eased long-term contracting between farmers and buyers, permitting futures contracts and reduced the role of ‘mandis’ - India’s state-run markets and government’s interventions in ‘essential’ commodities.

The jury is out whether these reforms will be able to adequately address these pain points.

The protests might seem paradoxical given agriculture’s recent performance. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Indian agriculture has been one of the country’s quiet success stories.

Meanwhile, the Indian economy as a whole contracted by 14.9% in H1 2020, agriculture grew by 3.4%. Agriculture also added 14 million jobs amidst overall reductions in employment. This success was due to a favourable monsoon, agriculture’s exemption from many lockdown restrictions and an increase in acreage under cultivation in many states as returnee migrants from COVID-19 impacted cities picked up farming activities.

What ails the Indian agriculture?

Though Indian agriculture and the rural economy has widely proven itself to be resilient under today’s COVID-19 adversity, horrific levels of farmer suicides - some 34 per day owing chiefly to crop failure, debt burden and price crash - attest to deeper-seated and more structural malaise in the sector.

Close to 70% of the country’s population is dependent on agriculture (in stark contrast it only makes up around 15% of GDP) and 86% of farmers cultivate less than 2 hectares, which leaves hundreds of millions of farmers precariously dependent on their annual harvest. About 22% of Indian farmers subsist below the poverty line. Despite being a food surplus economy, India is 94th out of 104 on the Global Hunger Index.

Farmers’ despair should come as no surprise. The decreasing size of land holdings, dependence on monsoon, inadequate and skewed access to formal agriculture credit and technology, and failure to get remunerative prices in the marketplace have robbed most Indian farmers of any cushion against the vagaries of harvests and prices.

Rural areas are of course not just about food production; biodiversity, micro-climate and water availability all hinge on our land use choices and farmers need to steward these.

Doubling farmer incomes and reducing income volatility is not about reverting to status quo, but engineering change that builds farm level yield in a sustainable manner and remedies post-production inefficiencies.

Indian agricultural resilience: the elephant in the room

The South Asian climate is close to the maximum temperature limit for many cereal species and a warmer world means lower yields. Modelling studies have projected wheat yields to fall by 45% in South Asia.

A report by the Ministry of Agriculture submitted in 2017, suggests that climate change will impact productivity of most crops marginally by 2020. This could increase about 10% – 40% by 2100, unless appropriate adaptation measures are undertaken.

The Economic Survey in 2017-18 warned that, “Climate change could reduce annual agricultural incomes in the range of 15% – 18% on an average, and up to 20% – 25% for unirrigated areas”.

The Reserve Bank of India’s most recent Economic Review reports that average temperature rose by 1.8°C between 1997 and 2019. Over-abstraction of water has meant that 52% of wells (over 75% in Punjab and Haryana) have recorded a decline between 2008 and 2018. The sorts of physical disasters that can befall agriculture vary between states: Maharashtra and Gujarat - floods, Tamil Nadu - cyclones, Maharashtra - unseasonal rainfall and several south-east states - extreme heat.

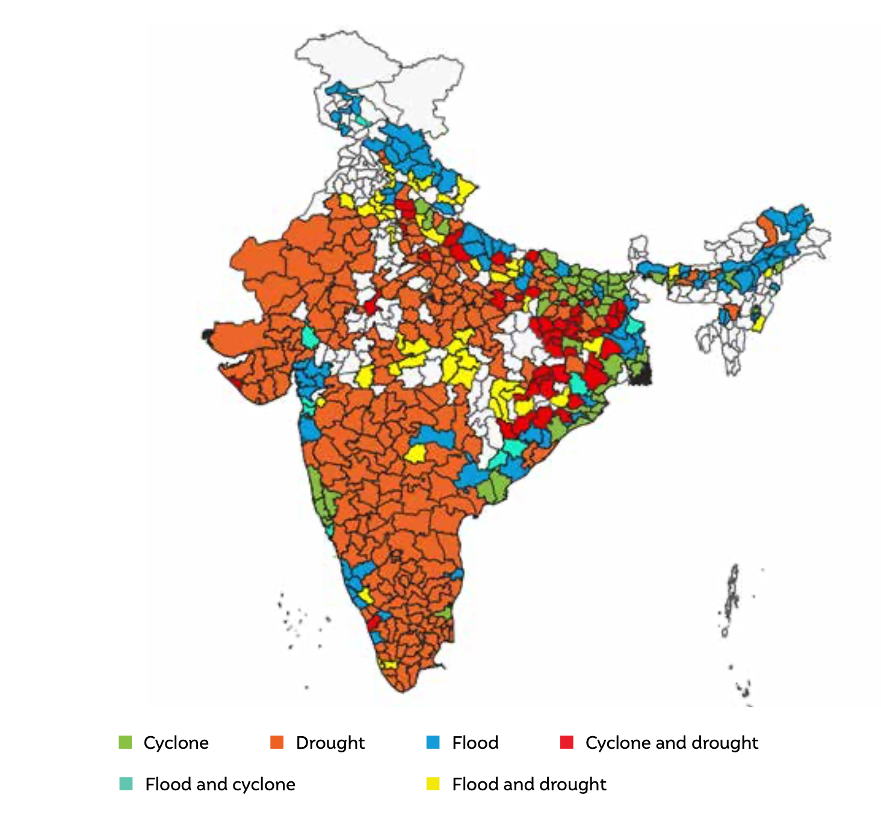

Vulnerability of different Indian districts to the physical effects of climate change

Source: Centre for Energy Environment & Water (CEEW), December 2020: “75% of Indian districts climate change hot-spots”

To date policy has encouraged the intensification of agriculture - especially of cereals. Policy was conceived in the 1960s when India was plagued by volatile crop prices and humiliating, sometimes tragic, shortfalls in food production. United States’ Public Law 480 (PL480) became emblematic of India’s inability to feed its population, and its reliance on foreign food aid.

But policies that favour intensification can actually increase climate vulnerability.

Farmers in Punjab and Haryana, who benefited from the green revolution now over-extract and pollute the ground water, abetted by free electricity and subsidised agro-chemicals. The majority of Indian farmers continue to earn subsistence incomes from small plots of land, remote from government’s buying agencies, and at the mercy of deteriorating farming conditions.

Agricultural resilience through interventions

The National Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) initiative seeks to enhance resilience of Indian agriculture through co-ordinated and strategic research and technology demonstration. Such research and related extension activities will yield crop varieties better equipped to handle more hostile future climates.

A wider range of interventions is needed to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

The picture above (from experiences in Brazil) shows broad categorisation of interventions. They have different levels of impact and do vary in different geographies and climatic conditions.

In the Indian scenario there is a need to have a combination approach which can include:

- improving upstream watershed management (to increase water retention and reduce soil erosion),

- adopting agricultural techniques that restore soil fertility,

- conserving water,

- selecting cultivars and species better suited to new climates,

- improving storage and on-farm processing to reduce waste and increase distribution,

- deploying equipment to monitor soils and supplying farmers real time meteorological, and

- commodity price data and better distribution and marketing to increase the prices paid to farmers.

One key focus must be enhancing the quality of soil. Better soil management improves yield, retains water and reduces needs for artificial inputs.

Together these can stabilise and increase incomes.

Techniques to fortify the soil, include regenerative agriculture, organic farming, use of cover crops, permaculture and agroforestry. These increase the capacity of the farm environment to cope with external stresses like droughts and floods. These can also reduce the cost of inputs and increase the income and profit margins for farmers, and can complement government’s financial support, e.g. through the crop insurance scheme Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bhima Yojana.

Investing in resilient agriculture

The interventions described above need investment in physical assets: check dams, terracing of hill-slopes and on-farm storage; crop loans to allow diversification of crops, and money for extension services to train farmers in new practices.

According to the eponymously named committee, doubling of farm incomes needs doubling of investment. Public and private investment in agriculture (and allied sectors) was estimated at INR 64,410 crore and INR 279,066 crore respectively in 2016-17.

Enhancing agricultural resilience will need the mobilisation of public and private finance. Union and state governments have traditionally financed projects to enhance watershed capacity.

Public banks are obliged to provide farmers credit under their priority sector lending obligations and the government backed agricultural finance provider NABARD offers refinancing to other financial institutions. NABARD also administers many grants for specific government programmes.

Government can also look at the manner in which it supports farm incomes. The answer lies in thinking about the interconnections between productivity, equity, ecology, nutrition, and economics. Increasing investment in resilient agriculture does provide an opportunity to look at the picture more holistically.

Sources of finance & opportunities to scale up

There are international green and ESG investors and donors who are mandated to provide investment in areas that can credibly achieve SDGs including climate resilience. Diversifying funding will become more important in the post COVID-19 world when banks’ Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) would rise, and public sector finances become tighter.

Opportunities to make agriculture more resilient exist but they need to be communicated to stakeholders. Consumer demand will be an important pull factor.

COVID-19 saw a surge in demand for clean and organic food, giving a fillip to this market segment which according to IBEF, is expected to grow at a CAGR of 10% during 2015-25. This is estimated to reach Rs. 75,000 crore (USD10.73 billion) by 2025 from Rs. 2,700 crore (USD386.32 million) in 2015.

Ag-tech interventions, by enhancing information flows, help farmer preparedness for climate and price volatility. Startups working on farm digitalisation, improving supply chain efficiency, and precision agriculture have grown rapidly and are already attracting venture capital investment.

Among initiatives at scale, the Zero Budget Natural Farming in the state of Andhra Pradesh (AP-CNMF) has already converted 500,000 farmers to natural farming.

Studies prove that the practice has improved yields, conserved water, lowered input costs, improved soil health and stabilised incomes. States such as Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are also starting to take a cue.

The last word

Addressing the anxieties of farmers evidenced in the recent protests needs a joined up approach. A vital first step is defining what constitutes resilient measures, to provide a broadly consistent framework that can be commonly understood by farmers, lending institutions, investors and borrowers.

Concomitantly, efforts are required to explore the kind of capital mix and financing instruments that can meet the solutions, and to prime up and capacitate the diversity of stakeholders, including policymakers.

A project led by Climate Bonds, in collaboration with WRI seeks to showcase investible opportunities in Indian agriculture that provide climate and social resilience.

We will continue to explore this subject with a series of new blogs, the next one focusing on the taxonomic approach for identifying resilience investments in agriculture.

'Till next time,

Climate Bonds.