In May 2023, EU institutions signed the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will enter into application in its transitional phase in October 2023.

The CBAM tariff system places a levy on certain carbon-intensive goods (like steel and cement), equalising the price of carbon paid for EU products and the one for imported goods. Ultimately, therefore, the CBAM aspires to build a ‘green’ level playing field.

CBAM works together with the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), the world’s first and biggest international emission trading system, to reduce emissions while preventing the risk of carbon leakage (see more on carbon leakage below). The ETS represents one of the main EU policies to address climate change and the cost-effective reduction of emissions. The ETS works on the cap-and-trade principle; within this cap, companies buy or receive allowances that they can trade with each other.

Policies like CBAM will play an important role in decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors across the world. Climate Bonds has laid out how policymakers can use policies, including CBAM, to rapidly mobilise finance toward credible transition efforts in the steel and cement sectors. Learn more about how effective policy change can facilitate a global transition to a green economy in our 101 Sustainable Finance Policies for 1.5°C paper.

Why… The EU introduced the CBAM to better address the risk of carbon leakage.

Since the implementation of the ETS in 2005, there has been a persistent concern about carbon leakage. Carbon leakage is when corporations relocate their production abroad, redirect their investment, or lose market share to foreign manufacturers due to the carbon cost imposed on them in their jurisdiction. This could happen as their production would become uncompetitive with lower-cost, higher-emissions imports (which don’t have a local carbon price equivalent).

As the EU Commission seeks to phase out free allocations in this era of higher climate ambition, the CBAM was proposed in 2021. While the allocation of free allowances under the ETS has been effective in addressing the risk of carbon leakage it has a major downside in that it dampens the incentive to significantly invest in greener production in the EU and non-EU countries (why would you if you get free emissions allowances?).

How … does the CBAM work?

The final agreement on the CBAM design was reached in December 2022. It will cover iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, hydrogen and other downstream products, as well as indirect emissions under certain conditions. Such changes make the CBAM more ambitious than the original proposal and bring some progress in levelling the playing field between EU and non-EU producers.

The final agreement on the CBAM design was reached in December 2022. It will cover iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, hydrogen and other downstream products, as well as indirect emissions under certain conditions. Such changes make the CBAM more ambitious than the original proposal and bring some progress in levelling the playing field between EU and non-EU producers.

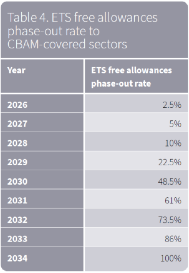

The CBAM will start applying in 2026 and will be fully phased in from 2035 – this means there is a big incentive for emitters to decarbonise their production processes in the first years, see the below table.

Importers will start paying the CBAM financial adjustment in 2026. Several countries such as Canada and the UK are also considering similar initiatives and a CBAM is already in place in California, where an adjustment is applied to certain imports of electricity.

The main obligation lies with importers who need to declare and purchase CBAM certificates to cover the emissions associated with CBAM-covered products. This sets a carbon price aimed at imports of non-EU products equivalent to the one paid by EU producers for making the same products. However, should EU importers demonstrate that they have already paid a carbon price to produce those goods in a non-EU country, this amount would be deducted, providing an incentive to decarbonise outside the EU.

Fabio Passaro, Climate Bonds Senior Transition Policy Analyst, says:

"The CBAM creates a strong incentive for producers to invest in low-carbon technologies now. For the hard-to-abate sectors, such as steel, the path forward is clear: a full green transformation is required to transition to net zero. Those that invest now to decrease emissions and plan to supply the steel required with the shortest possible environmental footprint will benefit from this competitive advantage"

How much… Companies are estimated to pay over EUR9bn in 2030 due to the CBAM.

To allow time to test this new system, the CBAM will be implemented gradually and only for a few sectors. The CBAM creates a strong incentive for producers to invest in low-carbon technologies now. For the hard-to-abate sectors, such as steel and cement, the path forward is clear: a full green transformation is required to transition to net zero. Those that invest now to decrease emissions and plan to supply the products required with the shortest possible environmental footprint will benefit from this competitive advantage.

At the time of the proposal, the EU Commission estimated that the yearly revenue stemming from CBAM will total EUR9.1bn in 2030 (EUR7bn from ETS auctioning and EUR2.1bn from CBAM). This amount will not only depend on the level of imports but also on the price of the EU allowances. The EU carbon price, established via the ETS, doubled in 2021 to EUR79.38/tCO2 on 20 December and reached the EUR100/t CO2 milestone in February 2023.

As the EU carbon price has already seen such an increase and more sectors are now covered by the CBAM (while others could be added in the next years), the amount that companies will have to pay in 2030 due to the CBAM is likely to be even higher than the initial EU Commission’s estimates.

At Climate Bonds, we have remained somewhat silent about emissions trading schemes' role in meeting climate commitments. This is, in part, because we have long seen them as part of the long game – important but in the short term, their impact may be constrained due to the limited number of countries and regions where there is an appetite to implement such schemes. The CBAM shakes things up a bit by getting incentivising exporter countries to consider carbon pricing or face higher tariffs. While we are yet to see the full implications, the idea is promising.

'Til next time,

Climate Bonds