A call for ambitious building decarbonisation measures in Europe

Buildings account for over a third of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions; the International Energy Agency estimates that 38% of the emission reductions we need to achieve by 2050 will have to come from the built environment.

Yet to date, making Europe’s buildings more energy efficient has been painfully slow. Most of the gains so far have been delivered through technological efficiencies – mainly more efficient boilers, switching to LED lighting and smarter heating controls.

Now that the low hanging fruit has been picked, there is a desperate need to tackle the big issue: that 75% of Europe’s buildings are classed as inefficient and will need an energy efficiency renovation by 2050 if the EU is to meet its Net Zero targets.[1]

On 23 January, the Industry, Research and Energy Committee MEPs will be called on to vote on the key legislative plank of the EU’s building decarbonisation strategy, the revision of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

Climate Bonds is calling on MEPs to ensure that the revised text lands in a place that is bold, ambitious and pushes Member States along the path of seriously tackling the renovation challenge.

Minimum Energy Performance Standards are an important trigger for renovation

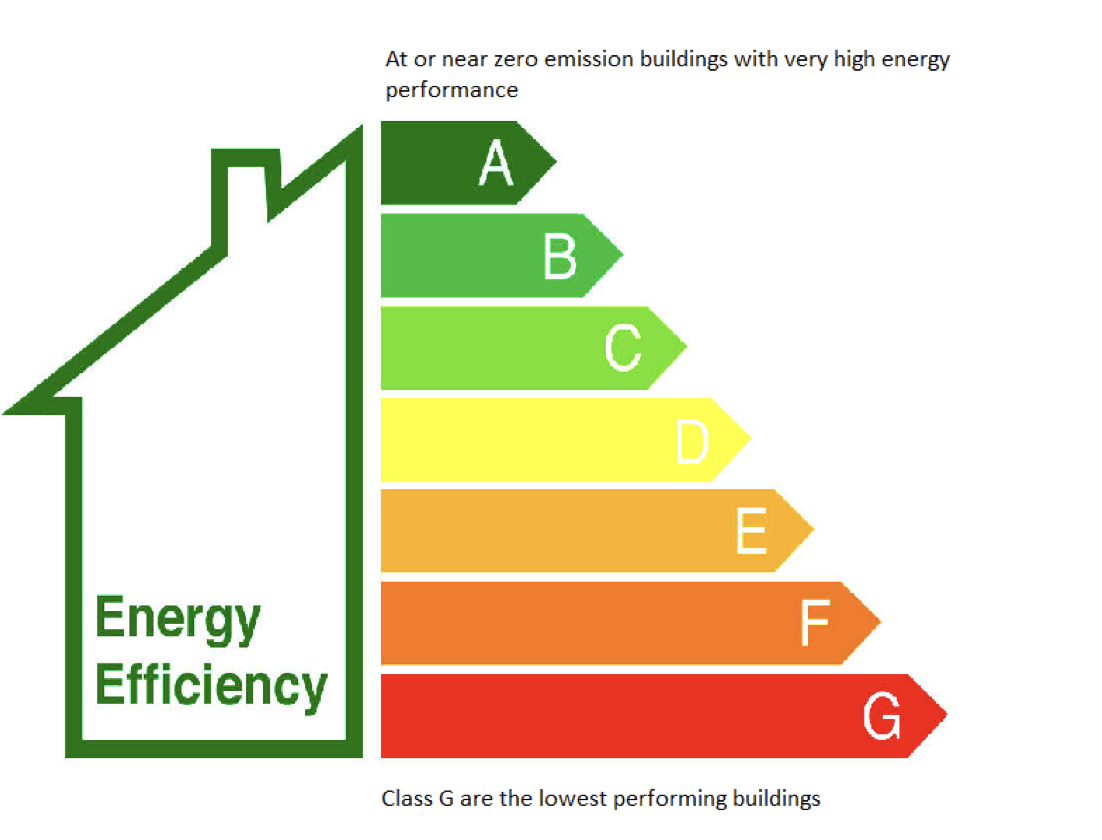

The Commission’s initial proposal was arguably quite tame, with many Member States already planning to move faster. The bar for mandating renovation of the worst performing buildings, through Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS), is being set so low that only 15% of buildings (those in Class G) would initially be covered[2].

Upgrading the existing building stock is particularly important for Europe. Whereas emerging nations might focus their efforts on tightening regulation and codes for new buildings, in Europe it is estimated that 85-95% of the existing building stock[3] will still be standing in 2050, underlining the need for a major programme of renovations.

Figure 1: The EPC Scale

Yet there are signs that some Member States are seeking to water down even the above proposal[4]. Hungary, Slovakia, and Croatia are reported to have been the most vocal in asking for more flexibility in the rules, but as many as 17 Member States may have joined this coalition in the Council.

States in this ‘flexibility coalition’ tend to be those that have fewer Energy Performance Certificates (EPC) registered to date or have an existing building stock on the lower end of the performance scale.[5]

Climate Bonds is supporting the EPBD Rapporteur[6] MEP Ciarán Cuffe, who set the ambition higher[7] by amending the Commission proposal to target EPC Class C by 2030 for public and non-residential buildings, and 2033 for residential.

Figure 2: Commission proposal compared to Rapporteur’s proposal for existing buildings

|

|

EPC Targets |

By 2027 |

By 2030 |

By 2033 |

|

Commission Proposal |

Public and non-resi buildings |

Class F |

Class E |

National timelines* |

|

Residential buildings |

|

Class F |

Class E |

|

|

Rapporteur’s Proposal |

Public and non-resi buildings |

Class D |

Class C |

National timelines* |

|

Residential buildings |

|

Class D |

Class C |

* Article 9(1) would require Member States to establish specific timelines for buildings to achieve higher energy performance classes by 2040 and 2050

Unlocking EPC data challenges

Mortgage Portfolio Standards, which would require mortgage lenders to report on the energy efficiency of their mortgage books, are shaping up to be another battle ground in the negotiations. Banks have raised an objection to bringing in a mandatory system in the first instance, given challenges with accessing granular Energy Performance Certificate data (EPC) in some Member States[8].

We would like to see the EPBD text iron out these kinks by better addressing building labelling inconsistencies among Member States and then enabling data access and processing rights, allowing banks to access property-by-property energy performance data across all EU nations. This should enable any reporting barriers to finally be resolved. As the saying goes, what gets measured will ultimately get managed.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has also highlighted that differing definitions and methodologies for calculating EPCs across the Member States makes it difficult for lenders to be able to compare portfolios, and therefore their associated risk profiles. We support the ECB’s calls for greater harmonisation in EPC methodologies as this will enable lenders to take a more informed view of transition risks in their mortgage books and target renovation loans accordingly.[9]

A comprehensive framework of financial support and tools

Climate Bonds is largely focused on the financial tools needed to support emissions reductions. We see it is a plus that the revised EPBD highlights the need for Member States to put financial support in place to achieve its objectives.

A central part of the EPBD is that Member States will be required to produce a national renovation plan outlining their investment needs as part of the cycle of National Energy and Climate Plan negotiations with the Commission.[10] Climate Bonds urges MEPs to amend the EPBD to allocate EU funding on the innovation and scaling up of green technologies necessary to decarbonise Europe’s building stock.

In addition to making the best use of centralised funding, Climate Bonds also encourages Member States that have not already issued a sovereign green bond to consider how they can allocate funding for energy efficiency through a sovereign issuance.

Member States need to get creative when deciding what they can do to support private financial flows, whether through providing guarantees to mortgage banks, greening national development banks, channelling funding through EuroPACE-style[11] renovation-financing tools or offering grants and equity loans to cash poor households.

This is a crucial moment on the path towards a zero-emission building stock in Europe by 2050. Decisions taken today will have repercussions for years to come. Under the normal legislative cycle, the EPBD will not be due for another revision for five to eight years, meaning that the initial minimum energy performance standards will have begun to kick in. It is time for the EU institutions to take bold action.

[2] Note: Class G corresponds to worst performing 15% of buildings. Public and commercial buildings would be required to reach Class F by 2027, residential buildings by 2030.

[5] See, for example, X-Tendo Project research ‘Energy Performance Certificates: Assessing their status and potential’ (2020)

[6] A Rapporteur is essentially a European Parliamentary Committee Chair

[7] Rapporteur proposes that public and commercial buildings would be required to reach Class D by 2027, residential buildings by 2030. PR_COD_1amCom (europa.eu)

[9] See Para. 1.3 Opinion of the European Central Bank of 16 January 2023 on a proposal for a directive on the energy performance of buildings (recast) (CON/2023/2) (europa.eu)

[10] Commission text highlights the Recovery and Resilience Facility, Cohesion Policy, Just Transition Fund, Invest EU and forthcoming Social Climate Fund

[11] EuroPACE was a project which ran from 2018 – 2021 exploring tax financing for energy efficiency renovations in Europe Feasibility study for a financial instrument and a review of existing retrofit loan schemes (climatebonds.net)