“Prediction is difficult, especially about the future,” quipped Niels Bohr.

He might have added ‘and particularly about future climate change’.

Last month, the greening central banks network – the NGFS – published two reports to help its membership work with banks and insurance companies to develop coherent and standardised projections to help understand our exposure to climate risks. They were amongst a string of 2020 reports published by the NGFS focusing on climate impacts to the financial system.

The first publication NGFS Climate Scenarios for central banks and supervisors provides three representative scenarios:

- Orderly transition’

- ‘Disorderly transition’ and;

- ‘Hot house world’

The three scenarios combine projected physical climate change (rainfall, temperature) and economic policies variables (like carbon taxes, energy efficiency) stretching up to 100 years into the future in 11 regions.

These were developed by prominent climate scientists and economic modellers whose work is used by IPCC. As well as the scenarios, in the second report the NGFS’s Guide for Supervisors publication suggests a step by step process for bringing central banks and the financial institutions they supervise on the journey to include climate risks in their decision processes.

The need for speed

![]()

The scenarios feature carbon prices of $100/tCO2 by 2030 for an orderly transition and necessitate a carbon price of between $300/$700/tCO2 by 2050 in an orderly/disorderly world.

As a reality check, the current carbon price within Europe (with the highest carbon price in the world) is just $25/tCO2. NGFS is asking financial institutions to contemplate the impacts on their balance sheets of coal and gas being pretty much priced out within just ten years and a concomitant investment in clean technologies of $70 trillion in the next thirty years.

The hot house world

In the ‘hot house world’ scenario instead of carbon pricing successfully reining in emissions we are left with global temperature rises to 3.5°C by the end of the century, creating climate chaos across three generations.

The two transition scenarios manage to hold temperature rise to less than 2°C with only a limited short-term GDP cost. In these scenarios, there are still significant changes in climate: a rise of 27% in North India and a fall of -30% in Southern Europe for instance.

For real numbers-nerds, detailed data for each of the scenarios is also available.

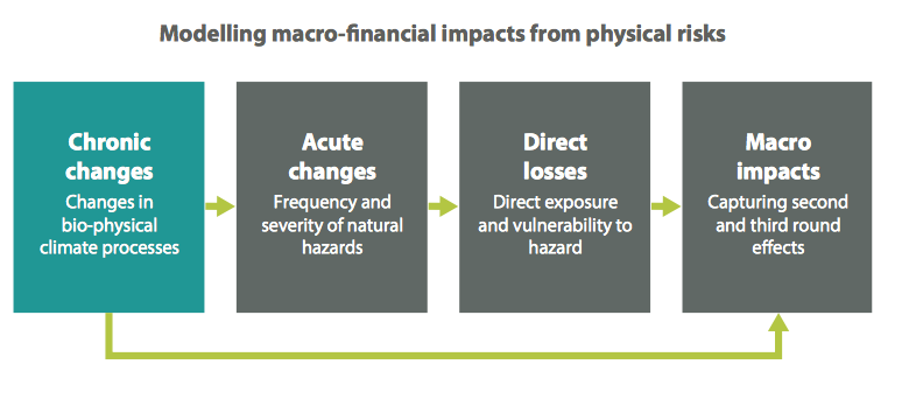

As we are so tragically witnessing with the torrential rainfall along the Yangtze river basin, there are few threats to financial stability. In turn, these give rise to loss of life, displacement of people, economic volatility, destruction of infrastructure, environmental agrcultural degradation.

Sadly as Bank of England analysts observe, banks’ current risk models are not incorporating observed climate risks into their pricing mortgage interest in flood prone areas. This is one of many examples where risks, both imediate and structural are yet to be incorporated into economic policy and investment patterns. It is also important that banks and insurers nudge business’ and people’s behaviour, so they invest and adjust their lifestyles to reduce their exposure to climate risks.

Source: NGFS -NGFS Climate Scenarios for central banks and supervisors

The evolution of stress tests

After the Global Financial Crisis, we increasingly used stress tests to ensure banks were capitalised to withstand plausible future economic shocks.

We now have to develop climate stress tests to ensure banks and the insurance companies are playing their part to shift capital from climate risky investment to climate saving investments.

![]()

In the UK, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) has asked banks and insurers to undertake just such a climate stress test. In Malaysia, the Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) has developed a principles based taxonomy to help banks distinguish between green and brown lending.

Learn more at the Webinar

Climate Bonds would like to invite you to a webinar with two leading central bankers, NGFS representatives, Sarah Breeden from UK PRA (Bank of England) and Jessica Chew from the Bank Negara Malaysia (Malysia Central Bank) discussing institutions efforts on this journey.

Thursday 23rd July 16:30 Kuala Lumpur, 10:30 Paris, 09:30 London

‘Till next time,

Climate Bonds