Magyar Nemzeti Bank asks domestic banks to reduce % rates on new green housing builds and retrofits

Until 18th December 2019, Hungary only impinged on the financial press when its half-son George Soros helped UK crash out of the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM) way back in 1992.

Last month it chalked up another noteworthy event when its central bank, Magyar Nemzeti Bank (MNB), became Europe’s first central bank to prefer green lending by offering favourable treatment for energy efficient housing loans. This is a significant step forward by a central bank in tilting the financial playing field towards green, as Climate Bonds has recently advocated.

Why the housing market?

Hungarian buildings account for 40% of the country’s energy consumption: per capita greenhouse gas emissions from the heating and cooling of homes put the country in the bottom third of EU countries.

Housing loans are many financial institutions’ largest asset class. Banks like holding residential mortgages because they provide a reasonable yield and since they are secured against a tangible asset, they are favourably treated in the determination of the banks’ regulated capital.

The 0.3% Differential

So how precisely is MNB encouraging green loans? The MNB is asking banks to reduce interest rates by 0.3% for loans to either purchase or construct energy efficient homes or undertake energy efficiency or renewable energy retrofits.

In exchange, lenders can hold less regulated capital [1] against qualifying loans effectively, thereby allowing banks to make more or bigger loans to energy efficient buildings with the same amount of scarce regulated capital.

However, this new ‘green supporting factor’ policy is unlikely to produce a huge surge in green lending. The discount on required capital MNB provides bank is modest: 5% for homes that are “BB” on their EPC and 7% for those that are “AA” or better.

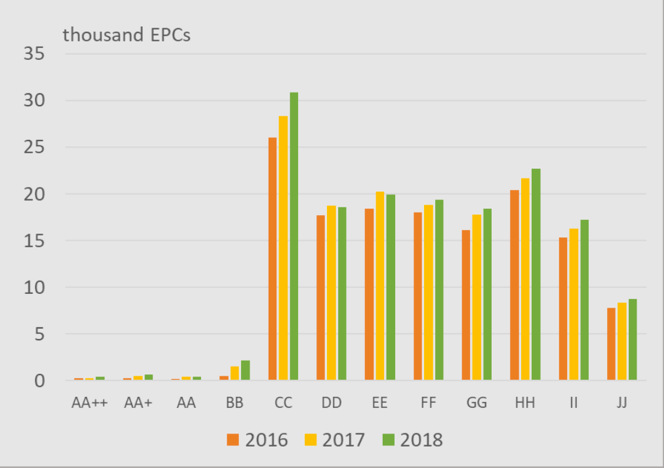

Also, the energy efficiency requirements for homes are very stringent requiring homes to be “BB” or better – homes that are near-zero in their energy use. Figure 1. shows that less than 5% of Hungary’s housing stock would currently qualify for this incentive.

Figure 1: Distribution of energy performance certificates (EPCs) of Hungarian building stock

The MNB Method & EeMAP

As interesting as the policy itself, is the manner in which MNB argues its case. Central banks are always nervous about introducing policies that reduce the capital held by institutions they prudentially regulate. What if there is a repeat of the global financial crisis and the value of assets held by banks collapse again and potential insolvency looms?

MNB therefore places a 1% overall cap on the total amount of housing (energy efficient plus non-energy efficient) backed lending can be increased through application of the energy efficiency discounts.

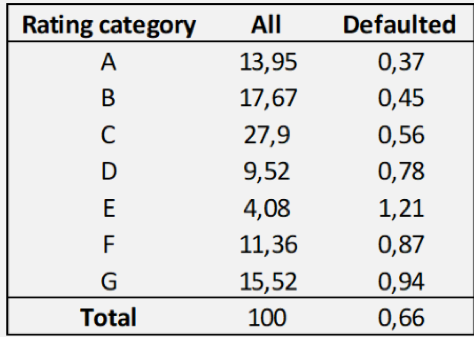

Secondly, MNB argues that the highly energy efficient homes are less likely to go into arrears and default and so objectively need less capital. MNB is therefore not giving the green an artificial helping hand, it is merely reflecting the lower riskiness of green mortgages.

It quotes analysis undertaken by the EeMAP Initiative which analyses mortgage default rates for different home energy efficiency ratings. Dutch mortgage data for 127,309 buildings is reproduced below. It shows the likelihood of A and B homes defaulting is about half that of less energy efficient homes.

Figure 2: Proportion of homes in each energy efficiency band and proportion defaulting

Source: Energy efficient Mortgages Action Plan (EeMAP)

The EU Taxonomy Appears

The other interesting feature to the policy is its use of the EU taxonomy to define green. MNB defined energy efficient homes as “AA” and “BB” which is equivalent to nearly-zero energy using buildings, echoing the EU taxonomy’s threshold. For energy efficiency renovations, qualifying individual measures are drawn from a list stemming from the EU taxonomy.

The Last Word

Hungary’s MNB is to be congratulated for being first EU central bank to introduce a green supporting factor policy. It did it deploying arguments consistent with its existing mandate as a prudential regulator.

Ironically, the Bank of England’s own economists undertook a more sophisticated econometric analysis of mortgage defaults than EeMAP and reached similar conclusions about relative default performance. But the Bank stopped there, only reporting its findings in a staff blog.

Perhaps the Bank of England’s Governor-elect Andrew Bailey can demonstrate continuity with his predecessors’ work on climate change by setting out plans to develop and introduce similar policies in the UK.

Even if UK’s Bank of England is not the first on board in introducing pro-climate policies in the EU, it hasn't missed the boat.

Anyone who’s successfully decoded the Hungarian Erno Rubik’s eponymous invention realises, success is not about solving just one side of problem but making sure the blocks are correctly lined up to tackle other faces of the puzzle.

‘Till next time,

Climate Bonds