Recent Aramco bond symbolises sanguine attitude of many investors to a 2050 world

Blog Post by Prashant Vaze, Head of Policy and Government at the Climate Bonds Initiative

The Aramco Bond and 2049

I often find the sanguine attitudes about climate change in the finance world unnerving, and several events in April were a particularly stark reminder of the gap in world views.

Early last month, Saudi Aramco raised USD 12 billion from its debut bond issuance. The longest dated tranche is for repayment in 2049. The coupon on these long-dated bonds is 4.375% which represents a spread over US Treasury gilts of 155 bp identical to long-dated bonds issued from other non-US A+ rated companies. The market evidently views Saudi Aramco as a safe long-term investment.

But hang on! By 2049 when the company has to return the capital back to investors, demand for the company products, if the international community’s Paris Agreement goes to plan, should be almost zero.

The issuance’s prospectus pointed out the company’s ultra-low cost of production, huge oil reserves - 336 billion tonnes of oil equivalent (around 10 years global demand for oil) and immense cash reserves (USD 49 billion). The document spent a few dutiful paragraphs trotting out boilerplate text on the risks from global climate mitigation policy and climate litigation.

But what did the document have to say about the company’s plans to mitigate its emissions? Almost nothing. There were plans to improve the operational energy efficiency, reduce flaring and utilise a tiny proportion of its huge CO2 emissions for enhanced oil recovery. Together these will reduce the company’s world beating production costs even further!

I had expected to see some nod in the prospectus to carbon capture and storage (CCS) providing a fig leaf of cover about how the business might survive in a net zero emissions world. But the only context the word “capture” appears in the prospectus is about the company’s attempts to move downstream and capture a higher value of the petroleum value chain.

The Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) were impressed and gave the company ratings of A1 (Moody’s) and A+ (Fitch) higher even than the Saudi government itself – indicating the unique position the company has in determining the health of the Kingdom’s finances.

Risk and Horizons

Investors seem prepared to turn a blind eye to the long-term threats to the company’s business model, its dubious ESG performance and focus on the bond’s low default risk and high yields. The bond was lapped up and reportedly ten times oversubscribed. The credit risk models run by agencies aren’t yet equipped to handle the political, greenhouse gas mitigation and migration risks that could beset the company (and the Kingdom) over the thirty-year time horizon.

Maybe we are asking too much from the CRAs? In my heart of hearts I couldn’t blame them. Their views conform to those of the broader industry. In February, BP published its energy outlook. Oil demand is forecasted to grow till 2030 and then plateau by 2040, justifying BP’s continued investment in exploration. No-one can accuse BP of being ignorant about climate change or climate mitigation risk. It’s just there is no compelling commercial reason for them to move away from their current business model.

Central Banks yet to face market failure

Later in April, I attended the Network for Greening Financial System (NGFS) meeting in Paris. The assessment of the threat from climate change was somber.

Frank Elderson, Chairman of NGFS, put it well: “The financial risks we face through climate change are analytically difficult, unprecedented and yet very urgent.”

But this urgency is not reflected in the speed or extent of interventions mooted by the NGFS in its recommendations.

In the “fireside chat” session three of the world’s top central bankers were asked to reminisce, as though it were 2040, about the role the Network had played in greening financial systems. Their mood wasn’t exactly complacent but there was a muted optimism that a steady improvement in the quality of companies’ climate disclosures would be sufficient. Disclosure of companies’ exposure and strategy would eventually lead to the correct pricing of risk.

They were so sure about the wisdom of the decision-making process governing the invisible hand, they even predicted the market forces would obviate the need for the NGFS altogether.

Central bankers were resistant about exceeding their mandates and using their powers to force capital to shift by imposing differential costs of finance for brown and green assets. Democratically elected governments should be responsible for determining the overall level of emissions and policies towards fossil fuel use, not unaccountable central bank boards.

The main concrete action, seen as realistic, was making the reporting framework (scenarios and stress tests) mandatory within the next five years. This would give time for voluntary disclosures to iron out the crinkles.

Sounds sensible? In five years, insurance companies and banks would have to show their exposure to climate risks.

I don’t want to downplay what a big deal this is. Its huge and welcome progress. But what if it isn’t enough? What if we don’t have time for the gradual step-by-step approach loved by prudent policy makers and we simply have to act on the imperfect data available at hand.

Extinction Rebellion see the emergency

The day after the NGFS meeting, I stopped to talk to an Extinction Rebellion (XR) protestor camped in Parliament Square in London. He was bemused to hear I had been working on climate change policy on and off all my working life, and all his life. He was born soon after 1992, the year the climate change convention was signed, which committed the richer countries to reduce their emissions and support poorer countries efforts to do the same. He had always lived with the existentialist threat climate change poses mankind.

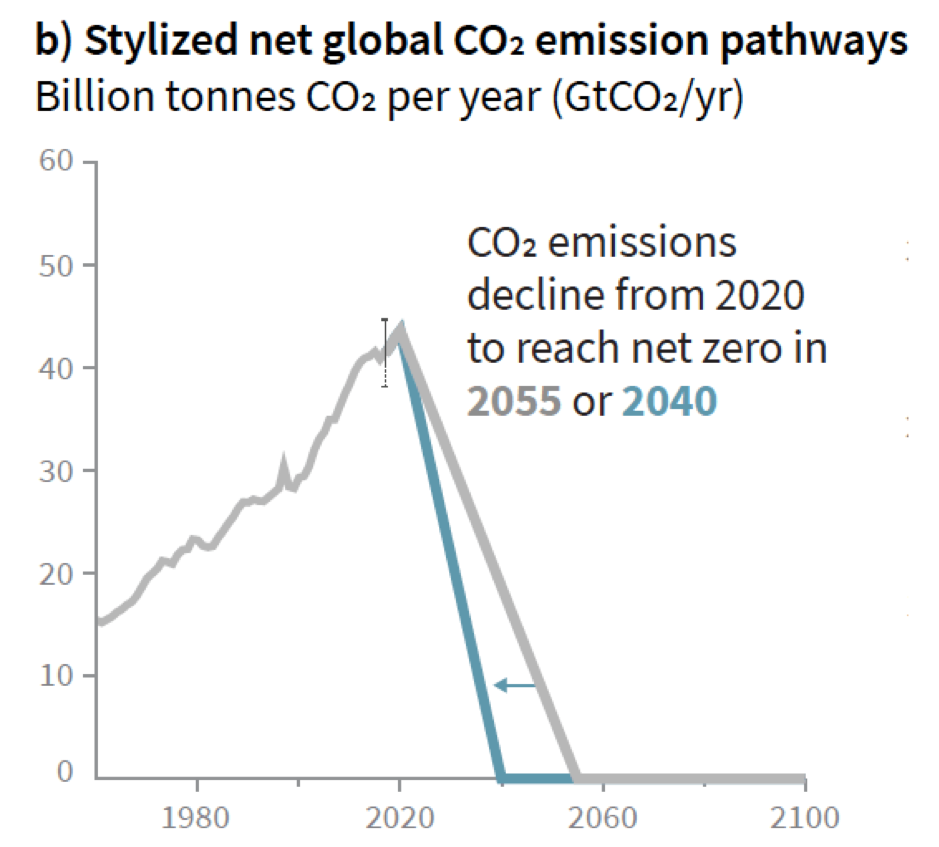

He asked me how I felt my generation had stewarded the environment? I think I failed to give him a satisfactory answer. I reproduce the graphic from the IPCC 1.5 special report which shows recent and projected emissions we need to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C

Source: IPCC, Special Report 1.5

Looking at the graph two things stand out. Firstly, it is apparent that climate change policy efforts haven’t achieved much. There is barely a dent in the rate of growth in GHGs emissions between 1970 and 1992 (when international climate policy kicked off) and the period thereafter.

The XR protestors can’t be blamed for asking what precisely has the world achieved in the last thirty years.

The other point to note about the graph is the trajectory proposed for the two scenarios (varying in society’s risk tolerance) for maintaining temperature rise to below 1.5°C: it’s viciously steep.

It requires a massive and immediate change in the way we use energy, we have to halve global emissions by 2030 in the more risk-averse trajectory.

The substance of what the XR protestors demand: government funded communication of the immediacy of the threat from environmental risks, a Net Zero carbon budget by 2025 and a Citizen’s Assembly to remove party politics from existential threats doesn’t seem so tall an order given how little has been delivered so far.

Throughout the young protestor’s life the threat of climate change has hung over us. Governments have failed to implement meaningful carbon pricing. They have axed government funded programmes to improve home energy efficiency that worked. They have continued to support land-use practices that subsidise livestock over trees.

The Last Word

The XR central challenge is that short-term political calculus has trumped the long-term rehabilitation of the global commons despite the increasingly shrill messages from science.

The Smiths make XR’s point well: When you say it's gonna happen "now", When exactly do you mean? See I've already waited too long. And all my hope is gone.

All I can say to the XR protestor is don’t lose hope. If we act quickly, use all the levers of power available, and stop waiting for someone else’s permission that we can still effect the necessary change.

That means all of us, even central bankers.

Prashant Vaze is Head of Policy and Government at the Climate Bonds Initiative.